Huixiang Research

Huixiang Sydney | Australia's "de facto marriage" (de facto) relationship

2023-11-10

In the last family law series, we said that Australia is cracking down on domestic violence. When couples, partners in a "de facto marriage" (de facto) relationship, relatives, etc. are subjected to domestic violence, they can apply for a domestic violence prohibition order to protect themselves. At the same time, in matters such as the division of property and the maintenance of children, couples in a "de facto marriage" (de facto) relationship have the same rights and obligations as couples in a registered marriage.

However, in Australia, many people do not know much about the "de facto marriage" relationship and the relevant provisions of "de facto marriage" in Australian family law. In this article, we will give a detailed explanation of the definition of "de facto marriage" and what kind of restrictions "de facto marriage" is subject to Australian family law.

Definition of a "de facto marriage" relationship

First of all, de facto means "de facto marriage", that is, couples do not have a certificate, but under certain facts and conditions, all rights and obligations between couples are equal to those of a certified couple. However, unlike domestic law, according to Australia's Family Law Act 1975 (cth) s 4AA (5), in Australia, a person can have both a formal registered marriage and a "de facto marriage" (de facto) relationship. At the same time, a person can have multiple "de facto" (de facto) relationships, and such "de facto" (de facto) relationships can exist in both heterosexual and same-sex couples.

In addition, under Family Law Act 1975 (cth) S4AA (1), the criteria for a "de facto marriage" (de facto) relationship are defined:

1. The two persons are not a licensed couple; and

2. The two persons are not related; and

3. Considering all the circumstances of the relationship, they are "lovers living together on a real family basis". The implication is to judge the nature of the relationship between two people, whether they are just dating, ordinary boyfriend and girlfriend, roommate, etc., or whether they want to establish a family life together.

S4AA (1) A person is in a de facto relationship with another person if:

(a) the persons are not legally married to each other; and

(b) the persons are not related by family (see subsection (6)); and

(c)having regard to all the circumstances of their relationship, they have a relationship as a couple living together on a genuine domestic basis.

The standard of "de facto marriage" (de facto) relationship

In Australia, different states/territories have different standards for the identification of "de facto marriage" (de facto) relationships and the documents that need to be provided. In New South Wales (NSW), for example, the "de facto marriage" (de facto) relationship determination first needs to meet the following conditions:

1. Both or at least one of them resides in the new state;

Over 2.18 years of age;

3. The parties are not in a marital relationship;

4. There is no kinship between the two parties;

5. No relationship with other people.

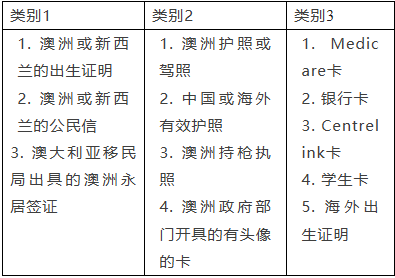

At the same time, the applicant needs to provide one of the following categories 1, 2, and 3. If the applicant cannot provide the materials of category 1, he can provide one item from category 2 and two items from category 3. If the applicant provides an overseas document, a translation issued by the Australian Translation Accreditation Authority is required.

The court ruled that the two parties were in a "de facto marriage" (de facto).

Relational Reference Factors

If the parties to a "de facto marriage" (de facto) relationship have not been certified, under the Australian Family Law Act 1975 (cth) s 4AA (2), the court will usually refer to the following factors when determining whether the parties are in a "de facto marriage" (de facto) relationship:

1. the duration of the relationship between the parties;

(B) the nature and extent of their common residence;

whether there is a sexual relationship;

4. the degree of financial dependence or interdependence between the two persons, and any financial support arrangements;

5. The ownership, use or acquisition of its property, I .e. whether the parties have common property;

6. The degree of common commitment to living together;

7. Whether the relationship has been registered as a prescribed relationship under the laws of the state or territory;

8. Whether the parties have children;

9. Reputation and public aspects of the relationship, I .e. whether or not the couple's relationship is made public.

For example, in the case of Beltran & Preston [2023] FedCFamC2F 514, the "husband" in a "de facto marriage" (de facto marriage) relationship stated that the "de facto marriage" (de facto marriage) relationship had broken up in June 2018, so the "wife" could no longer ask for alimony. But the "wife" argues that despite her move in 2018, they have remained in contact and have raised children together, so their "de facto" relationship should last until April 2021. After considering the following factors, the judge determined that the "de facto marriage" (de facto) relationship between the two parties had broken down in May 2018:

1. Ms. Preston has moved;

2. The parties have notified the Centrelink of the fact of their separation and the Centrelink has asked Mr. Beltran to take care of the child full-time;

3. The child has lived in a separate residence with Ms. Preston after May 2018;

4. Ms. Preston moved to Sydney to work alone; Ms. Preston paid more attention to Mr. Beltran's care for the children and suggested to Mr. Beltran that she personally take on the full-time care of the children, indicating that Ms. Preston did not want to live together.

Having considered all the matters set out above, I am satisfied that the parties separated in May 2018 (as asserted by Mr Beltran). In doing so, I have carefully reviewed all the elements of the parties’ relationship put before me (some consistent and some contradictory) as being part of the composite picture and have been influenced by the following conduct:

(a) Ms Preston moving out of the family home;

(b) the parties notifying Centrelink of their separation and the consequential arrangement for Mr Beltran to have full-time care of the boys;

(c) the boys spending time (or living with) Ms Preston in a separate residence after May 2018;

(d) Ms Preston re-locating to Sydney for work purposes on her own (despite an alleged expression by Mr Beltran that he would too);

(e) Ms Preston becoming so concerned about the care and support provided by Mr Beltran to the boys, that she suggested the boys come into her full-time care, being (essentially) a reversal of the boys’lived experience up until that time and certainly not being suggestive of them having a mutual commitment to a shared life; ……

Consequences when a "de facto marriage" (de facto) relationship breaks down

(I) attention to the timeliness of property division

In the event of a "de facto marriage" (de facto), the time limit for filing an application for division of property is two years from the date of separation of the spouses. Thus, a party in a "de facto marriage" (de facto) relationship must apply to the court for an order for the division of property within two years of the breakdown of the relationship. If the separation lasts for more than two years, an application for division of property can only be made with the permission of the court.

Factors to be considered in the division of (II) property

Typically, a spouse in a de facto relationship needs to prove that they have lived together for two years before they can apply to the court for a division of property. However, according to the provisions of Australia's Family Law Act 1975 (cth) S90SB, if the parties to the "de facto marriage" (de facto) relationship have one of the following circumstances, the court can also make a judgment on the property and other disputes between the parties to the "de facto marriage" (de facto) relationship:

1. Both have children;

2. The financial and non-financial contributions of the applicant are extremely large and would, if the court did not interfere, result in serious injustice to the applicant.

In addition, many people will misunderstand that after the "de facto marriage" (de facto) relationship breaks down, the two parties should distribute the property equally. However, due to the unique factors of each case, according to the provisions of Family Law Act 1975 (cth) S90SS in Australia, the court must consider the following factors when making a property division judgment:

1. financial contributions of both parties;

2. Non-financial contributions of both parties (e. g. contributions to the welfare of the family, care of children, etc.);

3. The financial situation of both parties (earning capacity);

4. Age and physical condition of both parties;

5. The custody of the child;

6. Whether either party will or is providing child support.

For example, in Re Estate Buxton; Knoll v Buxton [2023] NSWSC819, the judge mentioned that in deciding whether alimony, living expenses, etc. are sufficient (adequate) and proper (proper), the decision should be made on the basis of the specific circumstances of the case, not just on the basis of abstract legal rules.

What is “adequate” and “proper” in a particular case depends on the circumstances of the case; the concepts they embody are relative to those circumstances, not governed by an abstract absolute: Pontifical Society for the Propagation of the Faith v Scales (1962) 107 CLR 9 at 19 . The words “adequate” and “proper” connote something different. “Adequate” is concerned with quantum whereas “proper” is concerned with the standard of maintenance, education and advancement in life of the applicant for relief: Devereaux-Warnes v Hall (No 3) (2007) 35 WAR 127 at [72] –[77].

The division process of the proportion of (III) property division.

1. List the property under their respective names or jointly owned by both parties, such as houses, cars, businesses, investments, deposits, etc;

2. Divide the proportion of financial and non-financial contributions of both parties;

3. If the two parties jointly raise a minor child, after the two parties separate, the party living with the child may receive a certain proportion of the property. If one of the parties is unable to work or has no financial income, then this party may receive a certain proportion of the property.

(IV) Binding Property Agreement

In previous issues of the Family Law series, we talked about how a binding property agreement signed by a lawyer can reasonably plan family matters such as the property of both parties to a registered marriage, and the same applies to "de facto" (de facto) relationships. The parties to a "de facto marriage" (de facto) relationship can provide for the distribution of finances, debts, spousal support, etc. in the property agreement to reduce disputes arising from the breakdown of the relationship. However, if one party conceals significant property, the property agreement reached between the two parties is likely to be overturned in the future, or be ruled invalid.

(V) alimony, child support

According to the Australian Family Law Act 1975 (cth) S90SE, if one of the parties is unable to support himself after the breakdown of the "de facto marriage" (de facto) relationship, and the other party has the ability to support the party financially, then the party without the ability will be able to require the other party to provide alimony, until the party providing alimony marries or has a "de facto" relationship with another person in the future. At the same time, if both parties are raising children, the party caring for the children is entitled to financial support from the other party.

To sum up, in Australia, the "de facto marriage" (de facto) relationship refers to the fact that the couple is not licensed, but under certain facts and conditions, all the rights and obligations between the couple are equivalent to the licensed couple. For both parties in a "de facto marriage" (de facto) relationship, relationship authentication can be performed when certain conditions are met, thereby reducing subsequent problems to a certain extent. But if it is not certified, the court will consider the duration of the relationship, the nature and scope of the common residence, and whether there is a sexual relationship, etc. to determine whether the two parties are in a "de facto marriage" (de facto) relationship. At the same time, like registered marriages, "de facto" (de facto) relationships can also encounter problems such as property division and child support when they break down, so you can choose a binding property agreement signed by a lawyer to reduce subsequent disputes.

Note: The content of the above article is for reference only and does not constitute legal advice. If you have any legal questions, please consult with Huixiang Sydney lawyer in detail.

Related recommend

Lawyer Research Center, China University of Political Science and Law

Beijing Lawyers Association